Bending the Third Rail

Because We Should, We Can, We Do

Cost of the War in Iraq

(JavaScript Error)

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Nuclear Future

I just finished reading an essay by Graham Allison, a director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government who is the author of Nuclear Terrorism: The Ultimate Preventable Catastrophe (2004). The essay is a short analysis of the threat of a nuclear terrorist attack, as well as some suggestions of preventing one.

I just finished reading an essay by Graham Allison, a director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government who is the author of Nuclear Terrorism: The Ultimate Preventable Catastrophe (2004). The essay is a short analysis of the threat of a nuclear terrorist attack, as well as some suggestions of preventing one.I don't know Graham Allison from a load of wood. His reasoning seems sound and his essay appears well researched. So I'm going to assume for the time being that he's credible. One of the conclusions Allison reaches is that a terrorists nuclear attack is inevitable within the next decade.

Ok.

The initial effects of such an attack would be quite catastrophic, particularly psychologically. I say "psychologically" because despite an attack that kills thousands, the killing of mass numbers of human beings has occurred throughout history and is not unprecedented .... witness Dresden and Hiroshima not to mention numerous genocides perpetrated thoughout history that have killed millions. Be that as it may, the economic, social, civil and psychological impact of such a "new" attack would be enormous. Of course, much of Allison's focus is on how to prevent this. But let's assume for a moment that the nuclear genie is out of the bottle and let's further assume that efforts to stop proliferation fail.

I wonder if a nuclear attack is simply another step along an evolutionary trajectory of weapons? Certainly the invention of new, more efficient, and

deadly ways of killing each other is the norm throughout history. Yet, at each juncture we have had no choice but to adapt the reality of the existence of such weapons. Imagine the shock and awe experienced by the first victims of the bow and arrow, or when guns were introduced into warfare, or the shock and terror of the invention of artillery. If you've read any history, you know that giant battleships used to be awesome weapons that were used to subdue any enemy and inspired great fear when they showed up on the horizon.

deadly ways of killing each other is the norm throughout history. Yet, at each juncture we have had no choice but to adapt the reality of the existence of such weapons. Imagine the shock and awe experienced by the first victims of the bow and arrow, or when guns were introduced into warfare, or the shock and terror of the invention of artillery. If you've read any history, you know that giant battleships used to be awesome weapons that were used to subdue any enemy and inspired great fear when they showed up on the horizon.I submit that we are in the midst of that same adaptive process with nuclear weapons, even if on a much larger scale. The dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima was an enormous shock, inspiring fear among thinking people that man had created a weapon

of such power, not unlike the fear inspired by the development of past weapons. Since then, much has been done to limit the use of nuclear weapons and no others have been used. These attempts at weapons limitation are not without historic precedent. Unfortunately, history teaches us that the limiting of new weapons inevitably fails. Sorta like "if you build it, they will come" only it's more like "if you invent it, we will use it". Once used, the adaptive process (or grieving process if you will) begins starting with denial (we'll never use it again) to anger (they've used it and I'm afraid and angry!) to bargaining (maybe we can find a way to stop it from ever being used again) to depression (shit, no matter what we do, it gets used) to acceptance (well, I guess it's here to stay). I put us socially, generally, in the anger-bargaining stages, with groups of minority opinion in each of the five stages. All you have to do is listen to the Cheney administration's position on the use of "tactical" nuclear weapons in Iran to see the slow momentum shifting of the adaptive process.

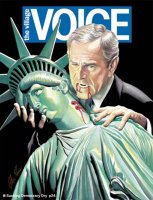

of such power, not unlike the fear inspired by the development of past weapons. Since then, much has been done to limit the use of nuclear weapons and no others have been used. These attempts at weapons limitation are not without historic precedent. Unfortunately, history teaches us that the limiting of new weapons inevitably fails. Sorta like "if you build it, they will come" only it's more like "if you invent it, we will use it". Once used, the adaptive process (or grieving process if you will) begins starting with denial (we'll never use it again) to anger (they've used it and I'm afraid and angry!) to bargaining (maybe we can find a way to stop it from ever being used again) to depression (shit, no matter what we do, it gets used) to acceptance (well, I guess it's here to stay). I put us socially, generally, in the anger-bargaining stages, with groups of minority opinion in each of the five stages. All you have to do is listen to the Cheney administration's position on the use of "tactical" nuclear weapons in Iran to see the slow momentum shifting of the adaptive process.I actually think there is a larger, more important question posed. Can liberty survive this particular process of adapting? I think not. A combination of many other factors, too numerous to get into here/now is at work softening up the body politic to give up liberty. We're at a point where a slight push over the edge of the cliff will send us spiralling down into some form of totalitarianism.

A terrorist nuclear attack is one possible force that could provide a quick nudge. Osama demonstrated that particular achilles heel with a few airplanes hitting a couple of buildings, killing a relatively small number of Americans (relative to what the international community experiences everyday). Can you imagine a terrorist even being caught with nuclear material in the U.S.?

A terrorist nuclear attack is one possible force that could provide a quick nudge. Osama demonstrated that particular achilles heel with a few airplanes hitting a couple of buildings, killing a relatively small number of Americans (relative to what the international community experiences everyday). Can you imagine a terrorist even being caught with nuclear material in the U.S.?I hope my pessimism is incorrect. Perhaps the need for liberty is stronger than the response of fear, at least in the long run. Our very very short history of liberty has been based in no small way on some freaks of geography, heritage and economics. But as the world shrinks and technology grows, lady liberty may be looking a little long in the tooth.

0 Comments:

About Me

- Name: Greyhair

- Location: Wine Country, California

I'm a very lucky person with every allergy known to man but still happy to be enjoying a wonderful life living in the best place in the world!

Blogroll

The Big PictureBillmon

Blah3.com

Born at the Crest of Empire

Eric Alterman

Eschaton

FireDogLake

Feingold's Blog

Dan Froomkin

The Huffington Post

Hullabaloo

The Illustrated Daily Scribble

Jesus General

Juan Cole

Matilda's Advice and Rants

Mia Culpa

MsJan Quilts

Needlenose

The Oil Drum

Political Animal

Political Wire

Spooks of the Ozarks

Talk About Corruption

TalkLeft

Think Progress

War and Peace

The Washington Note